Rumble Pie #10

Clover and Over Again

IN A PREVIOUS blog entry, Clover the Hills and Far Away, I discussed a style of literature, plays, poetry, and painting that was invented about five hundred years ago in Venice, Italy, known as 'pastoral'. In this blog entry, Part Two of my exploration into the origins -- and prejudices -- of the modern landscaping trade, I discuss how the exotic images in these pastoral paintings became the basis for a new movement in terraforming, and an corresponding ideology that has come to eclipse all other belief systems about the relationship between spaces and species.

UNTIL ABOUT THREE HUNDRED years ago, gardens were sculpted to be symmetrical, manicured to perfect proportions. It was the time that immediately preceded the French and American Wars of Independence; hereditary monarchs and aristocrats held sway over huge swaths of land, and they retained vast contingents of groundskeepers to take care of them. Green lawns didn't only look like carpets from down on the ground; from a bird's eye view, a topographical map of the land would closely resemble the kaleidoscopic patterns of a Persian rug.

THE MOST CLASSIC EXAMPLE of geography dissected into geometric designs is at Versailles. By this time, France was now the sole superpower operating in the European theatre; the self-styled Sun King Louis XIV relocated the seat of power from Paris, and commissioned edifice and landscape architects to transform Versailles into a complex capable of containing his entire court. The ultimate exemplar of a totally controlling potentate, Louis' vision for Versailles reflected his plan for France: absolute subjugation. People and plants were putty, and life was forced to imitate so-called art.

ON THE OTHER SIDE of the English channel, William Kent and Charles Bridgeman imagined a new kind of spatial relationship with nature. Bridgeman became the Royal Gardener of the British monarchs, but most of his clients were wealthy Whigs, nobles that opposed the power of the queen. He collaborated with William Kent, the designer who introduced who the work of Venetian architect Palladio to the now-newly-United Kingdom. Drawing on fantastic imagery in pastoral paintings, together they invented a new style of "landscape garden" that became famous across the continent as the eco-centric -- as opposed to ego-centric -- "English Garden".

WHAT WAS TRULY RADICAL and revolutionary about their approach to landscape design was that it attempted to replicate the organic patterns omnipresent in nature, and not the mathematical abstractions of an artificial orderliness imposed from above. Formalized architecture still held an important place in their integrated designs, but it no longer relegated the gaia goddess to a supporting role in her own realm. The humble grotto was elevated to an important position on par with the acropolis. It was still only accessible to the richest of the rich, but at least it shattered the angular orthodoxy of the time.

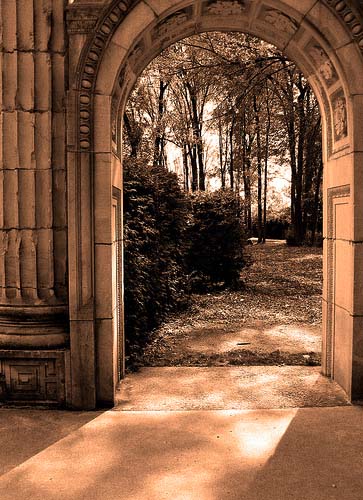

THE ENGLISH GARDEN became the basis for embellishing a piece of property in the American and Canadian colonies. In the industrial era, there were technological and economic factors that affected how this model was adopted and adapted to the twentieth century; I will deal with these in Part III of Green Grass 101: Clover and Out. And I'll close this entry with a photo album of Toronto's best example of a still-existing English Garden, Guildwood Park, at the World War One-era Guild Inn on the Scarborough Bluffs. It's a great place to take a date on a sunny summer day, a place where the colossal corinthian columns get overtaken by even taller timbers.

|