Rumble Pie #23

Intersections and Interventions

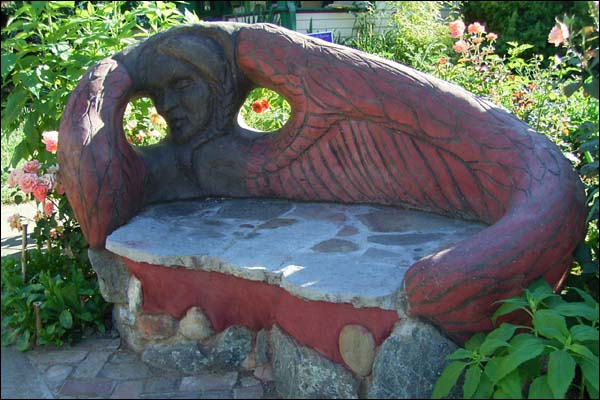

AS I ALLUDED TO IN OUR previous blog entry The Healthiest Housing in the World, earth may be the best possible material for building walls with, but it doesn't mean that that's all you can use it for. If the modern mud building movement was born in the temperate rainforests of rural Oregon, then the capital of urban earthen architecture is the state's most populous city, Portland. Country homes made from Cascadia Cob have been built out in the woods for the last twenty-five years, and mud structures on city streets have existed for half of that time. Obviously, land comes at a great premium in the city centre, and almost all properties are already occupied by brick buildings. It's hard to find an empty space to squeeze a new house into, and then once you find your narrow little plot of land, it's even harder to justify constructing something on it that has at least eighteen-inch-thick walls. Not to mention that in those days, when next to no building officials had even heard of earthen homes, it was hard to get them to sign off on the engineering. So a new initiative started up around building benches out of earth.

THERE IS ANOTHER SERIES of factors that led to the rise of the trend of bench-building. If you've ever been off the continent and strolled through a town in Tuscany or a village in Nigeria, you will have probably spent a good amount of time in piazzas: the plaza, platz, place. The narrow city streets are like arteries and veins that naturally flow in and out of the piazzas, the internal organs of the body urbana. There is where people congregate, trade, gossip, proselytize, flirt, fall in love. In summary, the piazzas are the hearts of the city (like multi-tentacled octopi, healthy cities have several hearts) -- not the location where the social contract is signed and sealed, but the place where it's written and rewritten daily, finger-painted and mud-sculpted, danced and sung, unorchestrated beautiful symphonies of flesh and bone. In cobblestone squares, the clock tick-tocks to the beat of the human footsteps and the click-clack of human-powered bicycles; cars and trucks and noisy engines of all sorts are banished to the periphery, where they cannot dominate the physical discourse. Now, where can these piazzas be found in the North American landscape?

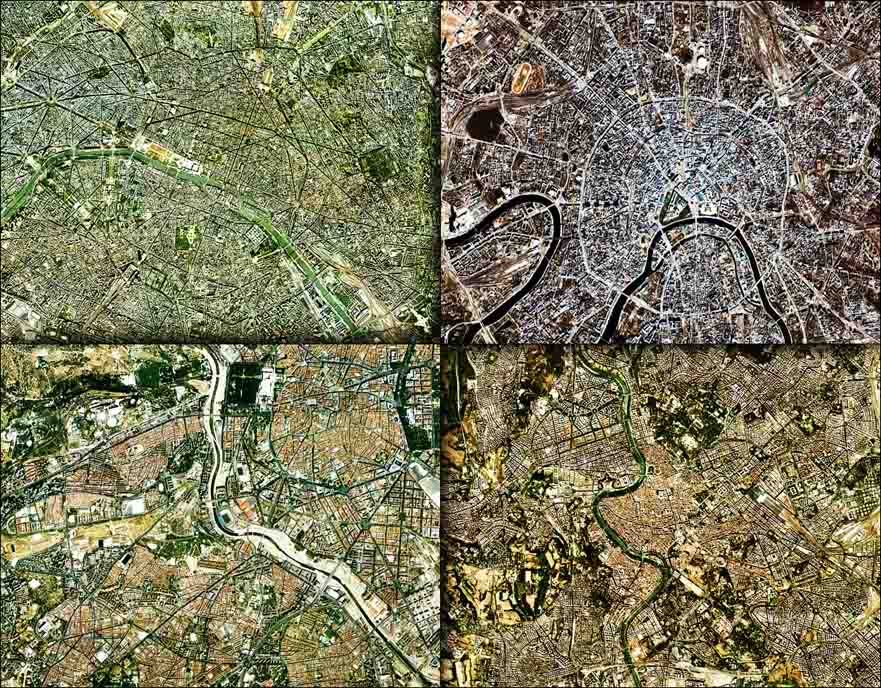

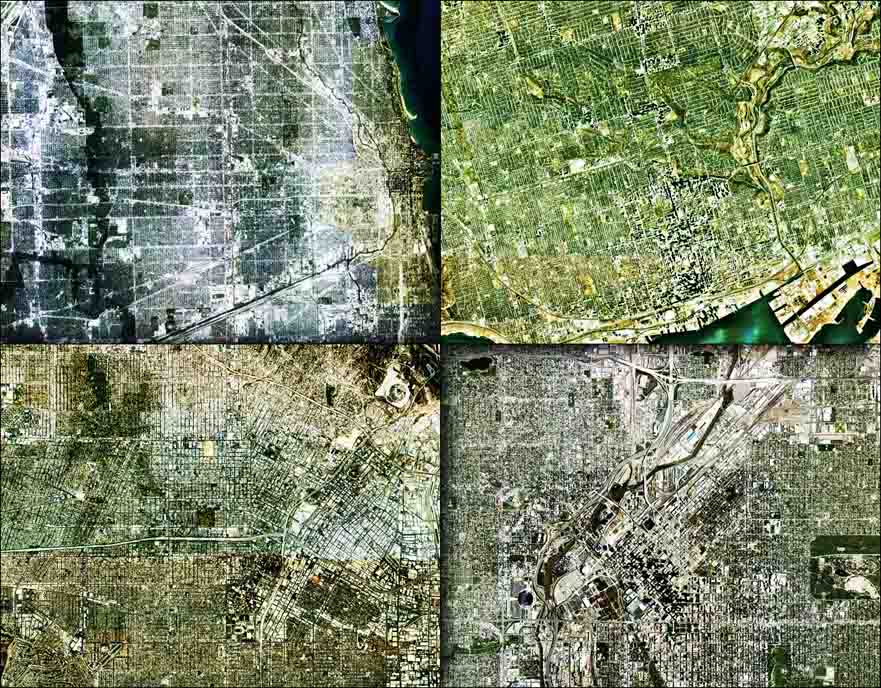

THE SAD ANSWER IS THAT they are unfortunately absent from the cityscape in the US and Canada. Throughout the Old World, urban areas grew organically out of the medieval towns and villages that preceded them. Back in the day, houses were built haphazardly, based on the needs of the town's inhabitants, in consultation with neighbours that were knowledgable about social conventions and customs, and with local builders who had experience with the materials and the micro-climate. Over time, the topography of towns would not look too dissimilar from the watering holes of any other animal, as seen from above. But nowadays, in urban planning schools all across the continent, two cities are held up as extreme examples: super-sustainable Portland, Oregon and far-too-rigid Toronto. If nearly all North American cities are symmetrical, Toronto is almost Borg-like in its religious adherence to the grid. Parallel lines make for superior high-speed viaducts, but poor incubators of human relationships. So it comes as nearly no surprise and even less protest when motorists run over cyclists and pedestrians with impunity, and the corporate media circles the wagons around the wagons.

European Capital Cities, clockwise from top left: Paris, Moscow, Rome, Madrid

North American Capital Cities, clockwise from top left: Chicago, Toronto, Denver, Los Angeles

NOWADAYS, THE NATURE OF THE human occupation of the landscape is decided by undemocratic planning officials, an insulated bureaucracy of supposed experts. Like all other aspects of our society, what determines the outcome of how our city streets will be laid out, and what kinds of buildings will be permitted, is the arrangement that is most profitable to the top one per cent of the population. The most powerful people are most interested in ensuring that workers get as fast as possible to work, and as quickly as they can to the shopping mall to purchase more products from companies they own. As we speed up and down the corridors built specifically for cars, they make sure that we are inundated with all kinds of advertisements, as often as possible, to reinforce their automaton consumerist ideology. They don't want people slowing down to talk and get to know each other, learning to trust in one another, sharing and receiving freely, gaining confidence in themselves and in their ability to provide for their own needs. The end result: an urban infrastructure plotted by the cold hand of totalitarian capitalism, hostile to our most basic human impulses as social animals.

BUT WHAT IF YOUR GRANDMOTHER had a bench to sit on so she could walk halfway around the block and then take a rest? After catching her breath, she would have a conversation with some passers-by and share her knowledge of the neighbourhood's history. We should not have to pay for a cup of coffee just so we can rest our weary feet, we should be able to take a seat next to the sidewalk for free; it should be a guaranteed right, not a privilege! What if our street furniture wasn't spat out by an industrial process, made of plastic materials; what if it didn't have to advertise corporate logos and consumer products, blare out purchase orders at eye level? Instead, we should have furniture objects that were obviously made by real people, by human hands, with love and care and attention to detail. They should be comfortable and made from natural materials, colourful and playful; public space is our birthright, not a commodity! This is the City Repair revolution in Portland, Oregon: not only to build earthen furniture, but to do it where people's paths cross, to intervene in the urban machine with creativity and to contest the cold culture of enclosure.

I FIRST DISCOVERED THE eco-artistic placemaking movement in Portland back in 2004, and when I got back to town, I organized the construction of Toronto's first-ever Cascadia Cob bench. Peter came out and got his hands and feet wet, learned the technique and helped build the bench. Two years later, he was so inspired that he built a cob bench of his own right outside his house in East York. Now we're inviting our clients to imagine what their own homes might look like with the addition of a cute little cob bench. If you are moved by the hand-sculpted aesthetic of the cob, and you'd like to create a personal private zen retreat out of earth, then we can certainly work that into an overall design for your back yard. And if you want to contribute to the community as well, then we are eager and excited to help you incorporate an earthen bench into your front yard, one that faces the sidewalk and invites your neighbours to sit down and say hi. Either way, any cob structure is going to give you good vibes, knowing that it was made from all-natural materials without any unnecessary fossil fuels, and molded into whatever funky shape your happy heart desires.

|